Still Life

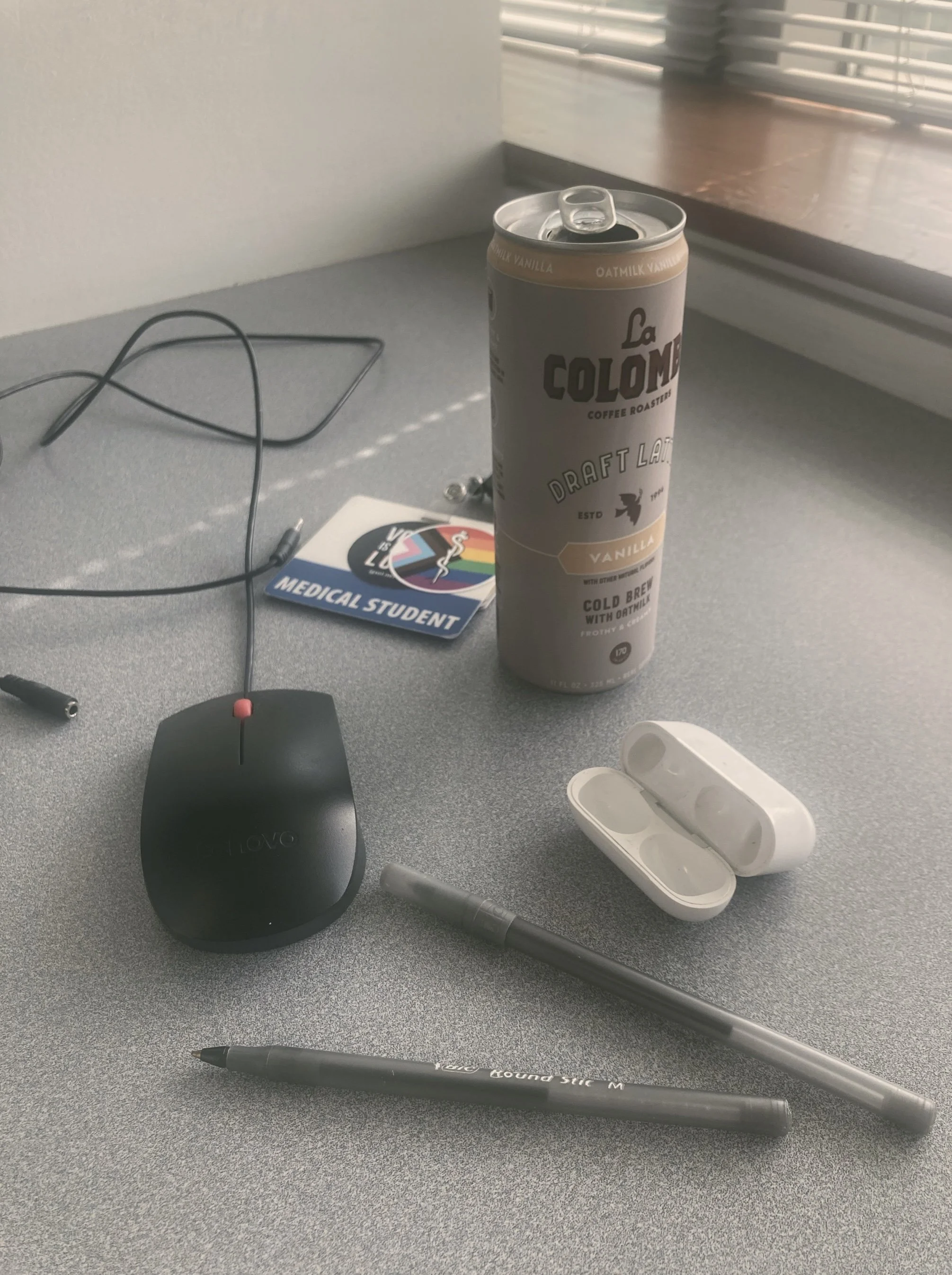

Image Description: A color photograph of a desk with scattered items, including a computer mouse, a can of cold brew coffee, a pen, a stylus, a pair of white wireless earbuds in an open case, and a ID badge with a rainbow sticker.

I am a medical student. I wanted to go into medicine so I could meet people where they are. Growing up, my mother was skeptical of vaccines and doctors in general; I saw how fear and mistrust can shape people’s health decisions. I understood how important it was to address these issues and increase health equity, especially for people in marginalized communities who do not trust the system – with reason!

Before beginning medical school, I worked as a medical assistant at a general surgery office. One patient was an 83 year-old woman who presented for breast cancer. When completing her intake and vitals, I asked her marital status. She responded that she was a widow and, to my surprise, she added that her wife passed away a few years prior. I hadn’t done or said anything extraordinary, but she must have felt safe with me, as she opened up. She told me about how they were together for 60 years. They attended protests together in the ‘60s, ‘70s, ‘80s… up until they were old and incapable of marching any longer. They got married the moment it was legal.

This patient stuck with me. Her queerness had nothing to do with her cancer or the reason she was seeking medical attention, but revealing this information helped me see her as more than her diagnosis. She was someone who has lived a full, rich, and courageous life. Her story reminded me that queerness is not a trend or a phase; it has existed and will continue to exist. I saw her truly, and her story as a human one. This is what it means to see the whole patient.

I have never been accused of being responsible or deserving of a highly stigmatized epidemic, for which vaccine development has lost funding. I have never experienced discrimination seeking gender affirming care – but I have heard accounts from friends and strangers alike about the barriers they have faced. Queer people must be persistent to receive the care they deserve, often turning to queer elders to fill the gaps in medical education. While this kind of community-building is beautiful, I see this as a failure of the medical system. Patients should not have to search for a safe doctor. That safety should be the standard.

This is why I have a pride sticker on my badge. Whether patients see this as a sign of my queerness or they interpret it as allyship, it is most important to me that it is visible. I want patients to be able to see this and know that I am safe to talk to and that I will be an advocate. I try to practice this now and I will carry it into my practice as a physician. Queer representation in medicine matters because every patient deserves to be seen in their entirety, and a small sticker can be the difference between being silent and feeling understood.